Character actor Larry Gates was the man who slapped Sidney Poitier onscreen – and was slapped back! That was the famous moment in In the Heat of the Night, and Gates was terribly proud to be what he said was probably the first white man ever slapped by a black man in a movie.

TV fans of an age to have lived the nightmare of nuclear annihilation scares in the Cold War era may remember him better for his appearance on the Twilight Zone: Gates portrayed a kindly, well-loved doctor who is faced with savage pleas from his neighbors, patients and friends to enter his family’s tiny bomb shelter during what appears to be an imminent missile attack.

When I visited Gates in 1996, he described his Twilight Zone performance of 35 years earlier as, “bug-eyed.” Harsh? He said he had a great deal of respect for the script and for the other actors in the production. But of himself he said, “You can never be too hard on yourself if you’re an artist. There is no forgiveness of sins in art. You do it the best you can and if you’re committed to your work, the audience knows that and they love to see you trying.”

When I visited Gates in 1996, he described his Twilight Zone performance of 35 years earlier as, “bug-eyed.” Harsh? He said he had a great deal of respect for the script and for the other actors in the production. But of himself he said, “You can never be too hard on yourself if you’re an artist. There is no forgiveness of sins in art. You do it the best you can and if you’re committed to your work, the audience knows that and they love to see you trying.”

He let me lift the Daytime Emmy he won in 1985 for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Drama Series – The Guiding Light in which he portrayed the irascible H.B. Lewis. (As everyone always says, the weight of those awards is much heavier than you expect.)

Lawrence Wheaton Gates was born September 24, 1915 into a staunch socially and politically conservative family in St. Paul, Minnesota. He recalled to me a Sunday morning in the kitchen with his mother when he was about 10 years old. He asked her why the family always told him and his younger sister stories against Jewish people. Mrs. Gates’ surprising reply was a wallop to the face hard enough to send him rolling across the room. As he rose to his feet, stinging from the blow, his mother told him he would understand when he grew up. He understood deeply; Gates was animated in the telling of the story. But stressed to me that he didn’t hold malice against his mother for the fiery incident nor against his family for any of the unyielding upbringing. I could see that that was true.

By his college years, Gates changed his major at the University of Minnesota from chemical engineering to psychology to speech. But upon graduation in the late 1930’s, the early words of his student advisor were still echoing in his head: “Admit it. You want to be an actor.”

Larry said a haunting, inescapable thing to me that many of us know and live with – “Everyone,” he said, “has artistic drive; but some are more afflicted than others.”

The progression of Larry’s affliction led him to a farmer he knew who let him ride in the caboose of a train shipping four carloads of hogs to the east. So, with a mere $25 dollars in his pocket, Larry Gates arrived in New York City. A good chunk of the money was gone after three nights of staying at the YMCA. So, he actually started sleeping in Central Park (safe then) and, he said, dined on peanuts for weeks before landing his first small role.

Gates lost his front hair early, enhancing his character actor aura. It was a consequence, he claimed, of the application of shoe polish. To achieve the look of an elderly man for a theatrical role, young Larry peered into his lighted make-up mirror backstage and slathered white shoe polish onto his hair. He recalled that he enjoyed drinking in the laughter of the audience but that he did not enjoy the process of watching his hair fall out from the effects of the shoe polish. It never grew back properly and resulted in the bald front so familiar to movie audiences who caught some of Gates’ 25 appearances in feature films: the balding small-town Southern doctor, for example, in the sultry 1958 Cat on a Hot Tin Roof; the officiously balding airline commissioner of the original Airport of 1970; or the deceptively comforting baldness of the psychiatrist-friend of the hero in Invasion of the Body Snatchers made in 1956.

Of that cult classic, I asked Gates if the actors had any sense of what an impact the film would have. He said they hadn’t a clue. It was shot in about 3 ½ weeks and was intended to be a “program filler” – just an unimportant second feature for a double bill. Yet, the phrase “pod people” is still almost as much a part of American vernacular as the phrase “the twilight zone.”

Back when he first returned home after serving in the Pacific as a commanding army officer during WWII, Gates actually considered giving up the financially risky life of an actor. But the old artistic affliction was too advanced. He was compelled to resume the risks. He had roles on most of the TV drama series of that era: The Alcoa Hour, Playhouse 90, Kraft Television Theatre, Hallmark Hall of Fame, Goodyear Playhouse and others.

His concept of those early days was that actors essentially ran the productions. Many producers, according to Gates, were not convinced that this new “thing” called television would last. And many directors and crew had experience mostly with stage and very little experience with cameras. But actors only needed to do what they already knew how to do – act. Productions would be rehearsed for a week or so, he said, but once the cameras started rolling, everything was live with no cuts and no retakes. So what the audience saw was mostly in the hands of the actors.

He entertaineded me with a couple of tales of gaffs in live TV. Larry’s character in one of those roles was supposed to smash a wine glass in anger. The prop crew had casually – and erroneously – set out a normal wine glass, not the breakaway glass called for. When it shattered at the dramatic moment the shards did their damage, leaving director, cast and crew helpless to intervene while Gates acted, gestured and bled all over the set. In another production for Westinghouse Summer Theatre, the scene called for Larry’s character to practice his golf swing. He got a hole in one – right through the camera lens, temporarily “blinding” the home viewer and forcing the production to stumble along, shot by the only remaining camera.

Larry’s television career itself went black after he publicly defended a fellow actor caught up in the Congressional anti-communist reign of terror. That man committed suicide. Gates’ impassioned outbursts – that resulted in 2 years of being banned from work in TV and film – had heated a Screen Actors Guild meeting. Years later in a letter to a friend Gates wrote, by contrast, about the moral stance of the theatre union. “Actors’ Equity,” he wrote, “never had any resolution attempting to control members’ political opinions and activities.”

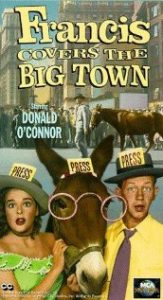

Film and television ultimately provided Larry Gates with a great deal of work for more than four decades and he claimed never to have taken a role that he regretted. But Gates’ first love – as is true for many actors of his generation – was always the theatre. He made his first New York stage appearance at age 24 in Speak of the Devil, was engaged in rounds of theatrical repertory and relished a couple of triumphant runs on Broadway. Perhaps less of a source of satisfaction was his first screen role as a reporter trying to arrange to have Francis the Talking Mule destroyed for some infraction the animal had committed in Francis Covers the Big Town released in 1953. He said the strings used to control Francis’ “talking” lips kept getting tangled.

Film and television ultimately provided Larry Gates with a great deal of work for more than four decades and he claimed never to have taken a role that he regretted. But Gates’ first love – as is true for many actors of his generation – was always the theatre. He made his first New York stage appearance at age 24 in Speak of the Devil, was engaged in rounds of theatrical repertory and relished a couple of triumphant runs on Broadway. Perhaps less of a source of satisfaction was his first screen role as a reporter trying to arrange to have Francis the Talking Mule destroyed for some infraction the animal had committed in Francis Covers the Big Town released in 1953. He said the strings used to control Francis’ “talking” lips kept getting tangled.

Larry Gates long favored the New England lifestyle. Back in ’52 – for what is now a pittance – he purchased the 60 acres of Connecticut land where I visited him and his sparkling-eyed wife Judith in their handsome, rustic home. He was just as outspoken in those crackling New England town meetings as he had been at the Screen Actors Guild; and he enjoyed vegetable gardening and cooking for friends like playwright Arthur Miller and poet/professor Mark Van Doren (whose son Charles was pivotal in the quiz show scandals of the 1950’s).

Via a perpetual commute to the west coast, Larry continued to make numerous guest appearances on TV – Judd for the Defense, The F.B.I., 12 O’Clock High – before landing on The Guiding Light.

On the CBS series Lou Grant, Larry made a guest appearance in 1979 playing a caring hospice doctor, having tender scenes with Geraldine Fitzgerald whose character was weakening from leukemia. So there is an irony that Larry Gates also weakened and succumbed to leukemia not long after my visit. But the day I was with him, back near the end of the last millennium, he talked of a future in which he envisioned film as obsolete and where media transmissions would be entirely electronic. He was an intelligent and visionary person, you see.

I once heard actor Laurence Fishburne talk about that glorious In the Heat of the Night slap moment. He referred to Larry Gates not by name, but merely as, “some old guy,” who slapped Sidney Poitier. And I thought, “Shame on you, Mr. Fishburne. Okay, you’re responding to the character; I understand that.” We all do. But at the same time, “You should have known the name of such a quality colleague and been able and pleased to refer to him by it.”

I don’t know whether my interview with him was the only time he ever used this word but Mr. Gates coined the term characterdom. I love that. It’s like stardom – but on a much on a different level. He said to me that character actors never have to worry, as leading men and leading ladies do, about fading into characterdom because they are already there. Aren’t we happy that they are? ~FW

<- Return to search