There is nothing ordinary about Wally Shawn – neither his oddball looks, nor the cartoon-like sibilance in his speech, nor his exceptional family, nor the density of his talents. Shawn may be a bit too name-recognizable to be amidst the Supporting TV Cast character actor roster – but maybe not.

He is currently a regular on the sitcom Young Sheldon but I remember him, from TV, most fondly for “Splat!” – his single episode of Sex and the City wherein he is first rejected by Candice Bergen then shows up later, touchingly supporting her on his arm at the funeral of a party girl. But he’s been around endlessly: a regular on Gossip Girl, the voice of Bertram on Family Guy, Zek on Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, and so on, all the way through time to the sitcom Taxi and even further back. If you ever saw the movie The Princess Bride you probably haven’t forgotten the villainous little Vizzini nor would you forget the lovable tyrannosaurus Rex from Toy Story, voiced by Wally Shawn.

I don’t remember actually having dinner with him (that reference just harkens to his intellectually provocative, unique and, I would say, “must see” early film My Dinner with Andre), nor sitting down with him to break bread at any meal. But I do remember staying in the same house with him for a couple of days.

And what a house it was – early 20th century novelist Edith Wharton’s famed mansion, dubbed The Mount, in the Berkshire Mountains in Massachusetts.

Born in New York City November 12, 1943, Shawn has a younger brother – a composer named Allen Shawn. In the summer of the bicentennial birthday of the U.S., this Allen had composed an off-beat opera that was produced by the Lenox Arts Center, which was using The Mount to house creators and performers while in production. The casts and creators of two or three shows were working and living in The Mount simultaneously. Allen’s opera was one company and I was in the cast of a crazy play called Never Mind; No Matter for which the audience was on its feet most of the time – a body of spectators snaking around through the house and the grounds of the estate to follow the scenes as the players swarmed from one location to another.

Wallace Shawn was already a known entity in New York at the time. Most of the cast of our show knew his name and I’m not sure now how I knew, before he arrived, what he looked like because I’d never seen him onstage and he had not yet made his film debut as Diane Keaton’s surprising ex-husband in Manhattan. He had certainly attracted attention as the playwright of an audacious work at the Public Theatre called Our Late Night which won an Obie. We were a little bit excited that our house-mate Allen was the brother of Wally Shawn and were hoping the elder Shawn would turn up to see the production.

Now, some say that The Mount is haunted. I believe the house has 40 bedrooms. I lived there for three weeks, sleeping alone in a shadowy room full of other empty beds (the property had been used as a dormitory by the Foxhollow School for Girls which vacated it shortly before the Lenox Arts Center took up occupancy; the estate is now run as a non-profit organization, open for public tours and events) and I never personally sensed a supernatural presence there. It was, however, the first house I ever stayed in where the drive up from the road is so long that any time you hear the sound of a car, you know it is someone coming to see the people in the house and not just a random piece of traffic passing nearby. Wallace Shawn must have come up that long drive. I did not see My Dinner with Andre until about 20 years after it was released but when I did finally see it, I realized instantly that the “Debbie” to whom Wally refers several times in the film with such warmth was the Deborah who arrived with him at The Mount. I remember they were both quiet when they were around the rest of us, never seeming to want to linger. The only hints I got of haunting at The Mount were in the depths of Deborah’s eyes. And in a long, undulating scream I heard coming from their room one evening.

Now, some say that The Mount is haunted. I believe the house has 40 bedrooms. I lived there for three weeks, sleeping alone in a shadowy room full of other empty beds (the property had been used as a dormitory by the Foxhollow School for Girls which vacated it shortly before the Lenox Arts Center took up occupancy; the estate is now run as a non-profit organization, open for public tours and events) and I never personally sensed a supernatural presence there. It was, however, the first house I ever stayed in where the drive up from the road is so long that any time you hear the sound of a car, you know it is someone coming to see the people in the house and not just a random piece of traffic passing nearby. Wallace Shawn must have come up that long drive. I did not see My Dinner with Andre until about 20 years after it was released but when I did finally see it, I realized instantly that the “Debbie” to whom Wally refers several times in the film with such warmth was the Deborah who arrived with him at The Mount. I remember they were both quiet when they were around the rest of us, never seeming to want to linger. The only hints I got of haunting at The Mount were in the depths of Deborah’s eyes. And in a long, undulating scream I heard coming from their room one evening.

Wally Shawn was born to intellectuals, is the sibling of an intellectual and is partnered with an intellectual. Much has been written about his toney background and education, and his emotionally masked upbringing. His mother, Cecille Lyon Shawn, was a journalist who had written for The New Yorker. His father, William Shawn, was that cultivated publication’s affectionately regarded editor for nearly two generations – during which he maintained an extra-marital, live-in love relationship with writer Lillian Ross. (I’ve just finished reading Ms. Ross’ memoir about her life during the affair titled Here But Not Here in which she says of the situation, “From the beginning, [Cecille] was a party to our arrangements…Our life was hardly a secret.” That openess about “the other woman” was not, however, to be extended to the Shawn children. Ross goes on later to report Wallace’s father saying that, “he was resigned to the fact that his children would grow up in an atmosphere of untruth.”) Wally’s brother Allen Shawn is not only a composer, as I said, but also a professor and author of two memoirs. I have read enough passages from Allen’s book Twin to be both moved by the content and serenaded by the thought compositions of these reflections on his autistic and long institutionalized twin sister, Mary.

I said Wallace is, “partnered with an intellectual.” By all accounts, four decades after I met them, Wallace Shawn and Deborah Eisenberg are still a firm couple. Eisenberg is a highly regarded fiction writer of sensitive prose that, from the snatches I have read, seems to carry the reader swerving across the edges of the literal and the surreal as fluidly as skate blades over ice. Maybe they were just having a rough weekend back then at The Mount, or maybe they are cemented by strife. I just remember hearing them yelling at each other a lot. Unseen but bickering – loudly – behind their closed bedroom door or off in a corridor somewhere out of sight.

There was one evening our cast decided to go into town to take in a movie. I believe someone asked Wallace and Deborah if they’d like to join us. They didn’t. But as we piled into the car, we could hear them having another argument inside the house. Everyone froze, suspended for a few moments as Deborah let out a prolonged scream that was absolutely Gothic. We’d never heard her do that before. I think everyone was momentarily unsure whether the sound was really coming from Deborah or from a paranormal source…and I probably never will be absolutely certain. But as the car began to pull off down the drive, the scream was sustained and trailing – like a sound that would have issued from the first Mrs. Rochester.

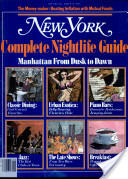

One of Shawn’s many plays is about a strife-riddled couple in his dark comedy Marie and Bruce, which was adapted to the cinema screen in 2004. In 1980, when venomous critic John Simon reviewed the original U.S. production – which he hated – in New York magazine he said, unnecessarily, that playwright Shawn was, “one of the worst and unsightliest actors in this city.” Shawn didn’t even appear in the play! A friend of mine was so outraged by that that she dashed off a letter to the editor and cancelled her subscription to New York.

One of Shawn’s many plays is about a strife-riddled couple in his dark comedy Marie and Bruce, which was adapted to the cinema screen in 2004. In 1980, when venomous critic John Simon reviewed the original U.S. production – which he hated – in New York magazine he said, unnecessarily, that playwright Shawn was, “one of the worst and unsightliest actors in this city.” Shawn didn’t even appear in the play! A friend of mine was so outraged by that that she dashed off a letter to the editor and cancelled her subscription to New York.

Shawn’s film and TV performances are full of mass appeal but his writings are often politically charged and are live wires of social consciousness. Broadcast journalist Laura Flanders caught up with him at an Occupy Wall Street demonstration in 2011. She later wrote that Shawn is a, “renown [sic] actor, author, playwright and thinker;” he had answered one of her questions through a wry little smile, saying that he did not want to live his, “one life…in a sewer of injustice.” I’d call that an apt metaphor off the top of one’s head. Still a thinker. Always a thinker. ~FW

Photo of The Mount courtesy of Leah Lee:

<- Return to search